This past month of April I had a bit of an adventure in server fires (though thankfully not literal) so I thought it might be interesting to share my experience, what I did, tools I used, discovered and created.

MY EBOOK£5 for Working the Command Line

Gain command-line shortcuts and processing techniques, install new tools and diagnose problems, and fully customize your terminal for a better, more powerful workflow.

£5 to own it today

Originally posted to my newsletter last month.

It started with a retirement notice…

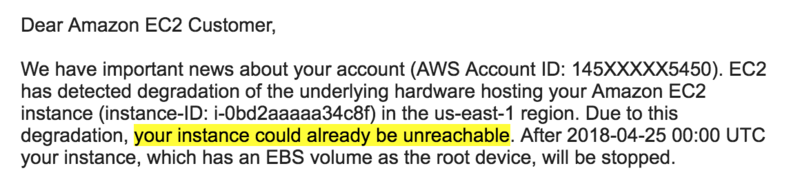

One morning a few weeks ago I got the following email from Amazon telling me an instance had been marked for retirement:

I've highlighted the "your instance could already be unreachable" because 6 hours prior that machine had been unreachable - according to my status monitors!

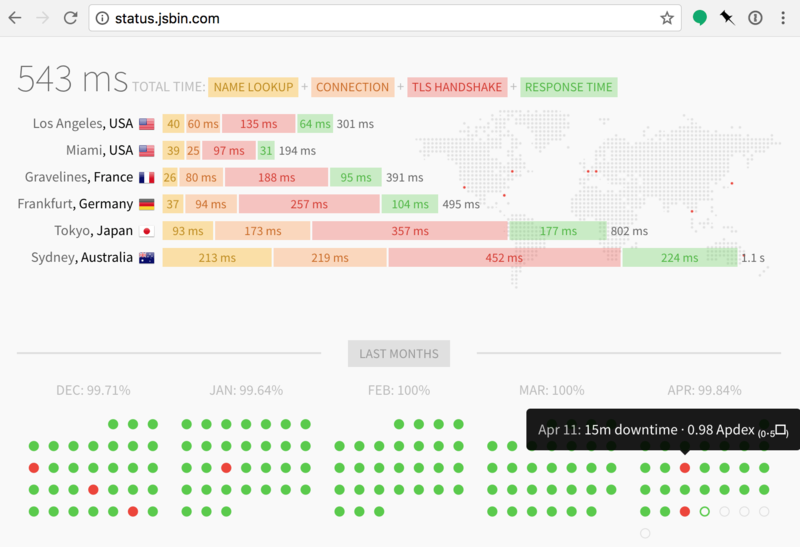

🛠updown.io is a fantastic and simple tool for monitoring uptime - then I have the notifications go via email and hit webhooks that I have setup to ping my lametric

Being a "normal" developer, I'm not an ops expert, so had to manually recreate the machine, and as it turned out, it was the main database server that had been hosed.

Foresight from previous burns

This isn't the first time the database server has exploded, so I had the foresight (perhaps obvious to you) to make sure the data for the database was stored on an entirely separate volume (so it could be mounted to a new machine if needs be).

In fact, the entire recovery process to getting the database running again took about an hour.

But what about when it happens again?

My database is a bottleneck

I run a fairly large MySQL database that requires a lot of memory (for something that you might consider reasonably simple from a tech stack perspective). In fact, it's the most expensive part of the JS Bin stack in AWS. Equally, every time someone loads the full output URL (like jsbin.com/foo/) the Node.js server goes to MySQL, gets the record, runs various checks (for permissions, etc), then runs each block of code through a transpiler (if required, i.e. markdown to HTML), then constructs it all as an HTML page, then returns it.

The obvious problem: these pages never change once the author is done with the bin. So why keep doing all that processing?

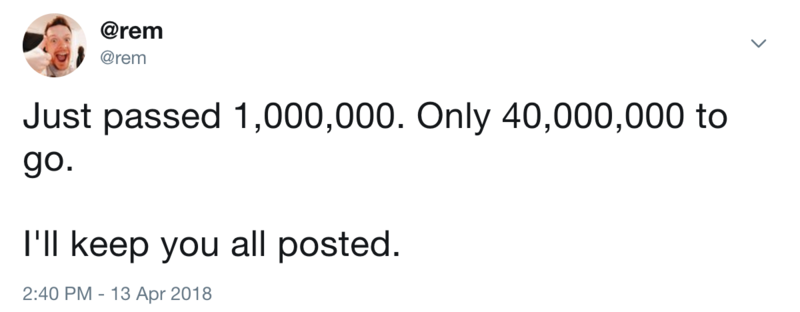

So if you've been following me on Twitter this last month, you'll have seen super interesting tweets like this:

I've written a script that is incrementally working its way through every-single-bin (of 42 million and change) and storing a static HTML file. That's stage one of The Grand Plan!

Storage options

I did a canvas of Twitter, and did a little reading around, and although my original plan was to store the static HTML for each bin in AWS' S3 service, I settled for Backblaze. It's a similar-ish service with very low costs.

To date I'm storing 111GB (36 million bins) and it'll cost me 10¢ a month. Hardly breaking the bank.

🛠backblaze.com - I'm using this to store all the static output from the 42 million bins (it also has node modules and a reasonably straight forward API)

The process of storing was a little tricky though. I started with a single CPU EC2 machine running through batches of 20 bins at a time, and the original estimate was the task would be complete in around 54 days. That's nearly two months!!!

The first job was to scale the machine to a multi-cpu instance (I went with 4 CPUs) so that I could shard the process across CPUs (which makes sense, but since Node is single threaded, you have to manage this yourself - I just use a modulus 4 on the bin.id and continued if it matched the job number).

The script I wrote is here which accepts a bin record and then attempts to transform the bin into HTML. The bin to HTML is another library that's used throughout old JS Bin and the new JS Bin - importantly the final output contains all the original source as well as the transpiled code. i.e. if you used markdown, then HTML is rendered, and there's a script[type="source/markdown"] included in the source (but hidden from the visitor). This is important because it'll serve me later on.

Inevitable crashing

Due to the nature of JS Bin, and allowing for processors like Pug (previously Jade), Less, SCSS and so on, the user code can run arbitrary JavaScript, including gems such as:

.columns

\- for (var i=0; i < 30; ++i)

.col

\- for (var i=0; i < 20; ++i)

.cell

…which, only results in an infinite loop and CPU going to >100%, which… 🤷 and then the export process eventually dies.

🛠screen is a unix tool that lets you run a session in the background that doesn't close when you end your own connection (tmux is a more powerful alternative). I ran 4 separate screens with individual logging. I wrote about screen a few years back.

So now I've got millions of static files, how do I get them out again? CloudFlare's workers.

🛠CloudFlare workers are (sort of) like cloud functions, but expose a service worker-like environment and let you do background fetches and pre-process incoming requests.

Retrieval and faking an API

I've got a new (temporary) domain jsbin.me pointing to CloudFlare, and I'm using CloudFlare's new worker service ($5/month for the first 10 million requests) to parse JS Bin URLs and to collect the source content from BackBlaze.

With a single script that follows Service Worker-like conventions (responding to fetch events), I'm able to proxy requests using the original URL format (and eventually I could swap out the original output.jsbin.com for this new system) to Backblaze and support more interesting requests like the source JavaScript, or CSS or even the pre-processed content.

For example:

- http://jsbin.me/vojilipite/2 the fully rendered static page

- http://jsbin.me/vojilipite/2.css rendered CSS

- http://jsbin.me/vojilipite/2.scss original (pre-processed) CSS panel content

- http://jsbin.me/vojilipite/2.api full bin object

This all comes from the static HTML file.

The tricky part is testing, but I wrote a tool that lets me replicate CloudFlare's worker environment so that I could even deploy my own cloud worker to a different hosting platform.

🛠cloud-worker is a node package that consumes a script with similar features of a Service Worker - and allows me to automate my testing for the CloudFlare worker

And that's the story so far! The export finished a few weeks back completing the 42 million bins and finding them a new home. As to what the next move is, and how I maintain that process going forward, I'm still unsure!